1173 A.D.

Anno gratiae M°C°LXX°III°, qui est

annus decimus nonus regni regis Henrici filii Matildis imperatricis,

idem rex fuit die Natalis Domini apud Chinonem in Andegavia, et uxor

ejus regina Alienor fuit ibi cum illo, et rex filius et uxor ejus fuerunt

in Normannia. Et post Natale misit rex pater pro rege filio, et profecti

sunt in Alverniam usque ad montem Ferrath; et illuc venit ad eos

Hubertus comes de Mauriana, et adduxit secum Aalays filiara suam primogenitam.

Quam rex pater comparavit ...

In the year of grace 1173, being the nineteenth year of

the reign of king Henry, son of the empress Matilda, the said king was, on the day

of the Nativity of our Lord, at Chinon, in Anjou, and queen Eleanor

was there with him, while the king, his son, and his wife were in

Normandy. After the Nativity, the king, the father, sent for the

king, the son, and they proceeded to Montferrat, in Auvergne, where

they were met by Hubert, earl of Maurienne, who brought with him

Alice, his eldest daughter. The king, the father, obtained her for

the sum of four thousand marks of silver, as a wife for his son John,

together with the whole of the earldom of Maurienne, in case the

above-named earl should not have a son by his wife. But, in case he

should have a son, lawfully begotten, then the

above-named earl granted to them and to their heirs for ever

Rousillon, with all his jurisdiction therein, and with all its

appurtenances, and the whole of the county of Le Belay, as he then

held the same; likewise, Pierrecastel, with all its appurtenances,

and the whole of the valley of Novalese, and Chambery, with all its

appurtenances, and Aix, and Aspermont, and Rochet, and Montemayor,

and Chambres, with the borough and the whole jurisdiction thereof.

All these lying on this side of the mountains, with all their

appurtenances, he granted to them immediately for ever. Beyond the

mountains, also, he gave and granted to them and to their heirs for

ever, the whole of Turin, with all its appurtenances, the college of

Canorech, with all its appurtenances, and all the fees which the

earls of Cannes held of him, and their services and fealties. Also,

in the earldom of Castro, he granted similar fees, fealties, and

services. In the Val D’Aosta he granted to them Castiglione,

which the viscount D’Aosta held of him, to hold the same for

ever against all men. All these the above-named earl granted to the

said son of the king of England for ever, together with his daughter

before-mentioned, as freely, fully, and quietly, in men and cities,

castles, and other places of defence, meadows, leasowes, mills,

woods, plains, waters, valleys, mountains, customs, and all other

things, as ever he or his father had held or enjoyed all the same as

underwritten therein, or even more fully and freely. Furthermore, the

said earl was willing immediately, or whenever it should please our

lord the king of England, that homage and fealty should be done by

all his people throughout the whole of his lands, saving always their

fealty to himself so long as he should hold the same. Moreover, he

granted to them and to their heirs for ever, all the right that he

had in the county of Grenoble, and whatsoever he might acquire

therein. But in case his eldest daughter above-named should happen to

die, whatever he had granted with the eldest, he did thereby grant

the whole of the same, as therein written, together with his second

daughter, to the son of the illustrious king of England.

That the covenants above-written should he kept between our

lord the king of England and the earl of Maurienne, both the earl of Maurienne

himself, and the count de Cevennes, and nearly all the other nobles

of his territory, made oath; to the effect that the earl of Maurienne

would inviolably observe the said covenants; and if he should in any

way depart therefrom, they made oath that, on the summons of our lord

the king of England, or of his messenger, and even without any such

summons, so soon as they should happen to know that the earl had so

departed, they would, from the time of knowing thereof, surrender

themselves as hostages to our lord the king of England, in his own

realm, wherever he should think fit, and would remain in his custody

until such time as they should have prevailed upon the earl to

perform the king’s pleasure, or have made an arrangement with

the king, to his satisfaction.

Furthermore, Peter, the venerable archbishop of Tarentaise,

Ardune, bishop of Cevennes, William, bishop of Maurienne, and the abbot

of Saint Michael, the Holy Evangelists being placed before them, at the

command of the earl, steadfastly promised that, at the will and

pleasure of the king, and at such time as he should think fit, they

would excommunicate the person of the earl, and place his lands under

interdict, if the earl should not observe the agreement so made

between them; that they would also do the same as to the persons of

the earl’s liegemen, and as to the lands of those through whom

it should be caused, that the agreement so made between the king and

the earl was not observed, and would hold those who should refuse to

keep the peace and their lands under interdict, until satisfaction

should have been made to our lord the king.

Our lord the king made these covenants and the grants above-written,

with and to the earl of Maurienne, and by his command the following made

oath that by him the same should be observed: William, earl of

Mandevule, William, earl of Arundel, Ralph de Fay, William de Courcy,

William de Hinnez, Fulk Paynel, Robert de Briencourt, William

Mainegot, Theobald Chabot, William de Munlufzun, Peter de Montesson,

and Geoffrey Forrester.

In addition thereto, it was to be understood that the earl

might give his second daughter in marriage to whomsoever he would, without too

greatly diminishing the earldom, after his eldest daughter should

have been married to the king’s son, either her lawful age

allowing thereof, or through the dispensation of the Church of Rome;

and that it should be lawful for her parents or for other persons to

give from the lands, for the safety

of her soul, without too greatly diminishing the earldom. Also, that

the king should make payment immediately to the earl of one thousand

marks of silver; and that as soon as he should receive the earl’s

daughter, the latter should have at least another thousand marks of

silver; and that whatever should remain unpaid of the five thousand

marks, the earl should receive the same when the marriage should have

taken place between the king’s son and the earl’s

daughter, either by reason of lawful age or through the dispensation

of the Church of Rome. But, if our lord the king, which God forbid,

should chance to die first, or should depart from his territories,

then, neither he nor they who, at his command had made oath and had

given any security to the earl, should be bound by the covenants

above-written, but only our lord the king, the king’s son and

his people.

Accordingly, a few days having elapsed, there came into the

territories of the king of England, on behalf of the earl of Maurienne, the

marquis of Montferrat, Geoffrey de Plozac, and Merlo, his son, the chancellor

of earl Richard, and Berlo de Cambot, and Peter de Bouet, his

castellans, together with Peter de Saint Genese, and Peter de Turin,

knights, and Geoffrey de Aquabella, and Ralph de Varci, burgesses.

Touching the Holy Evangelists, these persons made oath that they

would strictly cause the earl to observe the covenants made between

the king and the earl, as to the son of the king and the daughter of

the earl, in such manner as they had been lawfully entered into,

written, and understood. And, if he should not observe the same, they

made oath that, on the summons of the king or of his messenger, or

even without any such summons, if they should happen to know that the

earl had departed therefrom, they would, from the time of knowing

thereof, surrender themselves as hostages to the king in his own

realm, and would remain in his custody until such time as they should

have prevailed upon the earl to perform the king’s pleasure, or

have made an arrangement with our lord the king to his satisfaction.

The before-named envoys also made oath that the earl should not give

his second daughter in marriage until his eldest daughter should have

been united in marriage with the king’s son, either by reason

of being of lawful age, or through the dispensation of the Church of

Rome; unless by the consent and desire of our lord

the king he should in the meantime have given her in marriage to some

other person. They also made oath that, if the earl’s daughter,

or, which God forbid, the king’s son, should chance to die

before a marriage should have taken place between them, then the earl

should repay to the king the whole of the money, or act according to

the king’s will and pleasure relative thereto, or pay it over

to him to whom the king should assign the same ; and that they, the

parties making the said oath, would, if the king should so wish, and

at such time as he should so wish, surrender themselves as hostages

in his realm and into his power until such time as the same should be

paid. They likewise made oath that they would use their best

endeavours to obtain the grant of Umbert the Younger, in order that

thereby the king’s son might have Rousillon and Pierrecastel,

and whatever had been granted to him by the earl in the county of Le

Belay. But if Umbert should happen to refuse to grant the same, then

they made oath that the earl should give him lands in lawful exchange

thereof, according to the arbitration of the abbot of Cluse, and of

Reginald, archdeacon of Salisbury, or of other lawful persons thereto

appointed by the king, if they should not be able to be present.

After this, the king of England, the father, and the king,

the son, came together to Limoges; and thither Raymond, earl of Saint Gilles,

came, and there did homage to both the kings of England, and to Richard,

earl of Poitou, for Toulouse, to hold the same of them by hereditary

right, by the service of appearing before them at their summons, and

staying with them and serving for forty days, without any cost on

their part; but if they should wish to have him longer in their

service, then they were to pay his reasonable expenses. And further,

the said earl of Saint Gilles was to give them from Toulouse and its

appurtenances one hundred marks of silver, or else ten chargers worth

ten marks a-piece.

There also came to Limoges the earl of Maurienne, and desired

to know how much of his own territory the king of England intended to grant to

his son John; and on the king expressing an intention to give him the

castle of Chinon, the castle of Lodun, and the castle of Mirabel, the

king, his son, would in nowise agree thereto, nor allow it to be

done. For he was already greatly offended that his father was

unwilling to assign to him some portion of his territories, where he,

with his wife, might take up their residence. Indeed, he had

requested his father to give him either Normandy, or Anjou, or

England, which request he had made at the suggestion of the king of

France, and of those of the earls and barons of England and Normandy

who disliked his father: and from this time it was that the king, the

son, had been seeking pretexts and an opportunity for withdrawing

from his father. And he had now so entirely revolted in feeling from

obeying his wishes, that he could not even converse with him on any

subject in a peaceable manner.

Having now gained his opportunity, both as to place and occasion,

the king, the son, left his father, and proceeded to the king of France.

However, Richard Barre, his chancellor, Walter, his chaplain,

Ailward, his chamberlain, and William Blund, his apparitor, left him,

and returned to the king, his father. Thus did the king’s son

lose both his feelings and his senses; he repulsed the innocent,

persecuted a father, usurped authority, seized upon a kingdom; he

alone was the guilty one, and yet a whole army conspired against his

father; “so does the madness of one make many mad.” For

he it was who thirsted for the blood of a father, the gore of a

parent!

In the meantime, Louis, king of the Franks, held a great council

at Paris, at which he and all the principal men of France made oath to

the son of the king of England that they would assist him in every

way in expelling his father from the kingdom, if he should not accede

to his wishes : on which he swore to them that he would not make

peace with his father, except with their sanction and consent. After

this, he swore that he would give to Philip, earl of Flanders, for

his homage, a thousand pounds of yearly revenues in England, and the

whole of Kent, together with Dover castle, and Rochester castle; to

Matthew, earl of Boulogne, for his homage, the Soke of Kirketon in

Lindsey, and the earldom of Mortaigne, with the honor of Hay; and to

Theobald, earl of Blois, for his homage, two hundred pounds of yearly

revenues in Anjou, and the castle of Amboise, with all the

jurisdiction which he had claimed to hold in Touraine; and he also

quitted claim to him of all right that the king his father and

himself had claimed in Chateau Regnaud. All these gifts, and many

besides that he made to other persons, he confirmed under his new

seal, which the king of France had ordered to be made for him.

Besides these, he made other gifts, which, under

the same seal, he confirmed; namely, to William, king of Scotland, for

his assistance, the whole of Northumberland as far as the river Tyne. To

the brother of the same king he gave for his services the earldom of

Huntingdon and of Cambridgeshire, and to earl Hugh Bigot, for his

services, the castle of Norwich.

Immediately after Easter, in this year, [1173] the whole

of the kingdom of France, and the king, the son of the king of England, Richard

his brother, earl of Poitou, and Geoffrey, earl of Bretagne, and nearly

all the earls and barons of England, Normandy, Aquitaine, Anjou, and

Brittany, arose against the king of England the father, and laid

waste his lands on every side with fire, sword, and rapine: they also

laid siege to his castles, and took them by storm, and there was no

one to relieve them. Still, he made all the resistance against them

that he possibly could: for he had with him twenty thousand

Brabanters, who served him faithfully, but not without large pay

which he gave them.

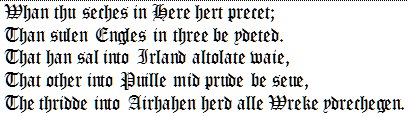

Then seems to have been fulfilled this prophecy of Merlin, which says:

“The cubs shall awake and shall roar aloud, and, leaving the

woods, shall seek their prey within the walls of the cities; among

those who shall be in their way they shall make great carnage, and

shall tear out the tongues of bulls. The necks of them as they roar

aloud they shall load with chains, and shall thus renew the times of

their forefathers.”

Upon this, the king wrote letters of complaint to all the emperors and

kings whom he thought to be friendly to him, relative to the

misfortunes which had befallen him through the exalted position which

he had given to his sons, strongly advising them not to exalt their

own sons beyond what it was their duty to do. On receiving his

letter, William king of Sicily wrote to him to the following effect:

“To Henry, by the grace of God the illustrious king of the English, duke

of Normandy and Aquitaine, and earl of Anjou, William, by the same

grace, king of Sicily, the dukedom of Apulia, and the principality of

Capua, the enjoyment of health, and the wished-for triumph in victory over his enemies. On

the receipt of your letter, we learned a thing of which indeed we

cannot without the greatest astonishment make mention, how that,

forgetting the ordinary usages of humanity and violating the law of

nature, the son has risen in rebellion against the father, the

begotten against the begetter, the bowels have been moved to

intestine war, the entrails have had recourse to arms, and, a new

miracle taking place, quite unheard of in our times, the flesh has

waged war against the blood, and the blood has sought means how to

shed itself. And, although for the purpose of checking the violence

of such extreme madness, the inconvenience of the distance does not

allow of our power affording any assistance, still, with all the

loving-kindness we possibly can, the expression of which, distance of

place does not prevent, sincerely embracing your person and honor, we

sympathize with your sorrow, and are indignant at your persecution,

which we regard as though it were our own. However, we do hope and

trust in the Lord, by whose judgment the judgments of kings are

directed, that He will no longer allow your sons to be tempted beyond

what they are able or ought to endure; and that He who became

obedient to the Father even unto death, will inspire them with the

light of filial obedience, whereby they shall be brought to recollect

that they are your flesh and blood, and, leaving the errors of their

hostility, shall acknowledge themselves to be your sons, and return

to their father, and thereby heal the disruption of nature, and that

the former union, being restored, will cement the bonds of natural

affection.”

Accordingly, immediately after Easter, as previously mentioned, the wicked fury of

the traitors burst forth. For, raving with diabolical frenzy, they

laid waste the territories of the king of England on both sides of

the sea with fire and sword in every direction. Philip, earl of

Flanders, with a large army, entered Normandy, and laid siege to

Aumarle, and took it. Proceeding thence, he laid siege to the castle

of Drincourt, which was surrendered to him; here his brother Matthew,

earl of Boulogne, died of a wound which he received from an arrow

when off his guard. On his decease, his brother Peter, the bishop

elect of Cambray, succeeded him in the earldom of Boulogne, and

renouncing his election, was made a knight, but died shortly after

without issue.

In the meantime, Louis, king of the Franks, and the king of England, the

son, laid siege to Verneuil; but Hugh de Lacy and Hugh de Beauchamp,

who were the constables thereof, defended the town of Verneuil boldly

and with resolute spirit. In consequence of this, the king of France,

after remaining there a whole month, with difficulty took a small

portion of the town on the side where his engines of war had been

planted. There were in Verneuil, besides the castle, three burghs;

each of which was separated from the other, and enclosed with a

strong wall and a foss filled with water. One of these was called the

Great Burgh, beyond the walls of which were pitched the tents of the

king of France and his engines of war. At the end of this month, when

the burghers in the Great Burgh saw that food and necessaries were

failing them, and that they should have nothing to eat, being

compelled by hunger and want, they made a truce for three days with

the king of France, for the purpose of going to their lord the king

of England, in order to obtain succour of him; and they made an

agreement that if they should not have succour within the next three

days, they would surrender to him that burgh. The peremptory day for

so doing was appointed on the vigil of Saint Laurence.

They

then gave hostages to the king of France to the above effect, and the

king of France, the king of England, the son, and earl Robert, the

brother of the king of France, earl Henry de Trois, Theobald, earl of

Blois, and William, archbishop of Sens, made oath to them, that if

they should surrender the burgh to the king of France at the period

named, the king of France would restore to them their hostages free

and unmolested, and would do no injury to them, nor allow it to be

done by others. This composition having been made to the above

effect, the burgesses before mentioned came to their lord the king of

England, and announced to him the agreement which they had made with

the king of France and the king his son.

On hearing of this, the king of England collected as large an army as he

possibly could from Normandy and the rest of his dominions, and came

to Breteuil, a castle belonging to Robert, earl of Leicester, which

the earl himself, taking to flight on his approach, left without any

protection. This the king entirely reduced to ashes, and the next

day, for the purpose of engaging with the king of France, proceeded

to a high hill, near Verneuil, with the whole of his army, and drew up his

troops in order of battle. This too was the peremptory day upon which

that portion of Verneuil was to be surrendered if it did not obtain

succour.

Upon this, Louis, king of the Franks, sent William, archbishop of Sens,

earl Henry, and earl Theobald, to the king of England, the father,

who appointed an interview to be held between them on the morrow; and

the king of England, to his misfortune, placed confidence in them;

for he was deceived. For on the morrow the king of France neither

came to the interview, nor yet sent any messenger. On this, the king

of England sent out spies to observe the position of the king of

France and his army; but while the spies were delaying their return,

that portion of Verneuil was surrendered to the king of France to

which he had laid siege. However, he did not dare retain it in his

hands, having transgressed the oath which he had made to the

burghers. For he neither restored to them their hostages, nor

preserved the peace as he had promised; but, entering the town, made

the burghers prisoners, carried off their property, set fire to the

Burgh, and then, taking to flight, carried away with him the burghers

before-mentioned into France.

When word was brought of this to the king of England, he pursued them with

the edge of the sword, slew many of them, and took considerable

numbers, and at nightfall arrived at Verneuil, where he remained one

night, and ordered the walls which had been levelled to be rebuilt.

But, in order that these events may be kept in memory, it is as well

to know that this flight of the king of France took place on the

fifth day before the ides of August, being the fifth day of the week,

upon the vigil of Saint Laurence, to the praise and glory of our Lord

Jesus Christ, who by punishing the crime of perfidy, so speedily

avenged the indignity done to his Martyr.

On the following day, the king of England, the father,

left Verneuil, and took the castle of Damville, which belonged to Gilbert de

Tilieres, and captured with it a great number of knights and

men-at-arms. After this, the king came to Rouen, and thence

dispatched his Brabanters, in whom he placed more confidence than the

rest, into Brittany, against Hugh, earl of Chester, and Ralph de

Fougeres, who had now gained possession of nearly the whole of it.

When these troops approached, the earl of Chester and Ralph de

Fougeres went forth to meet them. In consequence of this,

preparations were made for battle; the troops were drawn out in

battle array, and everything put in readiness for the combat.

Accordingly, the engagement having commenced, the enemies of the king

of England were routed, and the men of Brittany were laid prostrate

and utterly defeated. The earl, however, and Ralph de Fougeres, with

many of the most powerful men of Brittany, shut themselves up in the

fort of Dol, which they had taken by stratagem; on which, the

Brabanters besieged them on every side, on the thirteenth day before

the calends of September, being the second day of the week. In this

battle there were taken by the Brabanters seventeen knights

remarkable for their valour, whose names were as follows: Hascuil de

Saint Hilaire, William Patrick, Patrick de la Laude, Haimer de

Falaise, Geoffrey Farcy, William de Rulent, Ralph de Sens, John

Boteler, Vicaire de Dol, William des Loges, William de la Motte,

Robert de Treham, Payen Cornute, Reginald Pincun, Reginald de Champ

Lambert, and Eudo Bastard. Besides these, many others were captured,

both horse and foot, and more than fifteen hundred of the Bretons

were slain.

Now, on the day after this capture and slaughter, “Rumour,

than which nothing in speed more swift exists,” reached the ears of

the king of England, who, immediately setting out on his march

towards Dol, arrived there on the fifth day of the week, and

immediately ordered his stone-engines, and other engines of war, to

be got in readiness. The earl of Chester, however, and those who were

with him in the fort, being unable to defend it, surrendered it to

the king, on the seventeenth day before the calends of September,

being the Lord’s Day; and, in like manner, the whole of

Brittany, with all its fortresses, was restored to him, and its chief

men were carried into captivity. In the fortress of Dol many knights

and yeomen were taken prisoners, whose names were as follow: Hugh,

earl of Chester, Ralph de Fougeres, William de Fougeres, Hamo L’Espine,

Robert Patrick, Ingelram Patrick, Richard de Lovecot, Gwigain Guiun,

Oliver de Roche, Alan de Tintimac, Ivel, son of Ralph de Fougeres,

Gilo de Castel Girun, Philip de Landewi, William de Gorham, Ivel de

Mayne, Geoffrey de Buissiers, Reginald de Marche Lemarchis, Hervey de

Nitri, Hamelin de Eni, William de Saint Brice, William de Chastelar,

William de Orange, Ralph Waintras, Robert Boteler, Henry de Grey,

Grimbald Fitz-Haket, Geoffrey Abbat, John Guarein, John de Breerec,

Hugh Avenel, Hamelin de Pratelles, Swalo de la Bosothe, Secard

Burdin, Walter Bruno, John Ramart, Hugh de Bussay, Jerdan de Masrue,

Henry de Saint Hilaire, the brothers Hascuil, Bartholomew de

Busserie, Herbert de Buillon, Bauran de Tanet, Roland Fitz-Ralph,

Roellin Fitz-Ralph, Geoffrey de Minihac, Guido Butefact, Celdewin

Guiun, Ivel de Pont, Hamelin Abbat, Robert de Baioches, Elias

d’Aubigny, Reginald Cactus, John de Curtis, Philip de Luvenni,

Henry de Wastines, Henry de Saint Stephen, William Deschapelles,

Roger deB Loges, Bencellard de Serland, William de Bois Berenger,

John de Ruel, Oliver de MontBorel, Hamund de Rochefort, Robert de

Lespiney, John des Loges, Geoffrey Carlisle, Ralph de Tomal, Ralph le

Poters, Gilbert de Croi, Ralph Pucin, Matthew de Praels, Richard de

Cambrai, William le Francais, Oliver Rande, Ralph Ruffin,—Springard,

Roger de Chevereul, William des Loges, and many others, the names of

whom are not written in this book.

After these victories which God granted to the king of England,

the son of the empress Matilda, the king of France and his supporters fell into

despondency, and used all possible endeavours, that peace might be

made between the king of England and his sons. In consequence of

this, there was at length a meeting between Gisors and Trie, at which

Louis, king of the Franks, attended, accompanied by the archbishops,

bishops, earls, and barons of his realm, and bringing with him Henry,

Richard, and Geoffrey, the sons of the king of England. Henry, king

of England, the father, attended, with the archbishops, bishops,

earls, and barons of his dominions.

A conference was accordingly held between him and his sons,

for the purpose of establishing peace, on the seventh day before the calends

of October, being the third day of the week. At this conference, the

king, the father, offered to the king, his son, a moiety of the revenues of

his demesnes in England, and four fitting castles in the same territory; or,

if his son should prefer to remain in Normandy, the king, the father, offered

a moiety of the revenues of Normandy, and all the revenues of the lands that

were his father’s, the earl of Anjou, and three convenient castles in

Normandy, and one fitting castle, in Anjou, one fitting castle in

Maine, and one fitting castle in Touraine. To his son Richard, also,

he offered a moiety of the revenues of Aquitaine, and four fitting

castles in the same territory. And to his son Geoffrey he offered all

the lands that belonged, by right of inheritance, to the daughter of

duke Conan, if he should, with the sanction of our lord the pope, be

allowed to marry the above-named lady. The king, the father, also

submitted himself entirely to the arbitration of the archbishop of

Tarento and the legates of our lord the pope, as to adding to the

above as much more of his revenues, and giving the same to his sons,

as they should pronounce to be reasonable, reserving to himself the

administration of justice and the royal authority.

But it did not suit the purpose of the king of France that

the king’s sons should at present make peace with their father: in

addition to which, at the same conference, Robert, earl of Leicester, uttered

much opprobrious and abusive language to the king of England, the

father, and laid his hand on his sword for the purpose of striking

the king; but he was hindered by the byestanders from so doing, and

the conference was immediately brought to a close.

On the day after the conference, the knights of the king

of France had a skirmish with the knights of the king of England, between

Curteles and Gisors; in which fight Ingelram, castellan of Trie, was made

prisoner by earl William de Mandeville, and presented to the king,

the father. In the meantime, Robert, earl of Leicester, having raised

a large army, crossed over into England, and was received by earl

Hugh Bigot in the castle of Fremingham,* where he supplied him with

all necessaries. After this, the said Robert, earl of Leicester, laid

siege to Hakeneck, the castle of Ranulph de Broc, and took it; for,

at this period, Richard de Lucy, justiciary of England, and Humphrey

de Bohun, the king’s constable, had marched with a large army

into Lothian, the territory of the king of Scotland, for the purpose

of ravaging it.

* Framlingham, in Suffolk.

When, however, they heard of the arrival of the earl of

Leicester in England, they were greatly alarmed, and laying all other matters

aside, gave and received a truce from the king of Scotland, and,

after hostages were delivered on both sides for the preservation of

peace until the feast of Saint Hilary, hastened with all possible

speed to Saint Edmund’s. Thither also came to them Reginald,

earl of Cornwall, the king’s uncle, Robert, earl of Gloucester,

and William, earl of Arundel, On the approach of the festival of All

Saints, the above-named earl of Leicester withdrew from Fremingham

for the purpose of marching to Leicester, and came with his army to a

place near St. Edmund’s, which is known as Fornham, situate on

a piece of marshy ground, not far from the church of Saint Genevieve.

On his arrival being known, the earls, with a considerable force, and

Humphrey de Bohun with three hundred knights, soldiers of the king,

went forth armed for battle to meet the earl of Leicester, carrying

before them the banner of Saint Edmund the king and Martyr as their

standard. The ranks being drawn up in battle array, by virtue of the

aid of God and of his most glorious Martyr Saint Edmund, they

attacked the line in which the earl of Leicester had taken his

position, and in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, the earl of

Leicester was vanquished and taken prisoner, as also his wife and

Hugh des Chateaux, a nobleman of the kingdom of France, and all their

might was utterly crushed.

There fell in this battle more than ten thousand Flemings,

while all the rest were taken prisoners, and being thrown into prison in irons,

were there starved to death. As for the earl of Leicester and his

wife and Hugh des Chateaux, and the rest of the more wealthy men who

were captured with them, they were sent into Normandy to the king the

father; on which the king placed them in confinement at Falaise, and

Hugh, earl of Chester, with them.

On the feast of Saint Martin, king Henry, the father, entered

Anjou with his army, and shortly after Geoffrey, lord of Hay, surrendered to

him the castle of Hay. After this there were surrendered to him the

castle of Pruilly and the castle of Campigny, which Robert de Ble had

held against him. In this castle there were many knights and

men-at-arms taken prisoners, whose names were as follow: Haimeric de

Ble, Baldwin de Brisehaie, Hugh de Laloc, Hugh de Danars,

HughDelamotte, William de Rivan, Simon de Beniezai, John Maumonie, Hubert

Ruscevals, William Maingot, Saer de Terreis, John de Champigny, Walter de

Powis, Brice de Ceaux, Haimeric Bipant, Robert L’Anglais, Grossin

Champemain, Isambert Wellun, Geoffrey Carre, Payen Juge, William

Bugun, Castey, vassal of Saer de Terreis, Guiard, vassal of John

Maumonie, Roger, vassal of William Rivan, Peter, vassal of John de

Champigny, Philip, vassal of Hugh le Davis, Russell, vassal of Hubert

Ruscevals, Vulgier and Haimeric, vassals of Peter de Posey, Osmund,

Everard, and Geoffrey, vassals of Haimeric de Ble, Gilbert and

Albinus, vassals of Hugh de Laloc, Brito and Geoffrey, vassals of

Walter Powis, Haimeric and Peter, vassals of Hugh Delamotte, and

Brito and Sunennes, vassals of Simon de Bernezai.

In the same year, Louis, king of the Franks, knighted

Richard, the son of king Henry. In this year, also, Robert the prior of Dare, who was

bishop elect of the church of Arras, renounced that election, and was

elected bishop of the diocese of Cambrai, but before he was

consecrated was slain by his enemies.

In the same year, Henry, king of England, contrary to the

prohibition of his son, king Henry, and after appeal made to our lord the pope,

gave the archbishopric of Canterbury, to Richard prior of Dover, the bishopric

of Bath to Reginald, son of Jocelyn, bishop of Salisbury, the

bishopric of Winchester to Richard de Ivechester, archdeacon of

Poitou, the bishopric of Hereford to Robert Folliot, the bishopric of

Ely to Geoffrey Riddel, archdeacon of Canterbury, and the bishopric

of Chichester to John de Greneford. After this, at the time of the

feast of Saint Andrew, the king of England, the father, took Vendime

by storm, which was held against him by Bucard de Lavardin, who had

expelled therefrom his father, the earl of Vendime.

1174 A.D.

In the year of grace 1174, being the twentieth year of the reign

of king Henry, son of the empress Matilda, the said Henry spent the festival

of the Nativity of our Lord at Caen in Normandy, and a truce was made

between him and Louis, king of the Franks, from the feast of Saint

Hilary until the end of Easter. In the same year, and at the time

abovenamed, Hugh, bishop of Durham, at an interview held between

himself and William, king of the Scots, on the confines of the

kingdoms of England and Scotland, namely at Revedeur, gave to the

above-named king of the Scots three hundred marks of silver from the

lands of the barons of Northumberland, for granting a truce from the

feast of Saint Hilary until the end of Easter.

In the meantime, Roger de Mowbray fortified his castle at

Kinardeferie, in Axholme; and Hugh, bishop of Durham, fortified the castle of

Alverton. After Easter, breaking the truce, Henry, the son of the

king of England, and Philip, earl of Flanders, having raised a large

army, determined to come over to England.

In the meantime, William, king of the Scots, came into

Northumberland with a large force, and there with his Scotch and Galloway men

committed execrable deeds. For his men ripped asunder pregnant women,

and, dragging forth the embryos, tossed them upon the points of

lances. Infants, children, youths, aged men, all of both sexes, from

the highest to the lowest, they slew alike without mercy or ransom.

The priests and clergy they murdered in the very churches upon the

altars. Consequently, wherever the Scots and the Galloway men came,

horror and carnage prevailed. Shortly after, the king of the Scots

sent his brother David to Leicester, in order to assist the troops of

the earl of Leicester; but before he arrived there, Reginald, earl of

Cornwall, and Richard de Lacy, justiciary of England, had burned the

city of Leicester to the ground, together with its churches and

buildings, with the exception of the castle.

After Pentecost, Anketill Mallory, the constable of Leicester,

fought a battle with the burgesses of Northampton, and defeated them, taking

more than two hundred prisoners, and slaying a considerable number.

Shortly after, Robert, earl of Ferrers, together with the knights of

Leicester, came at daybreak to Nottingham, a royal town, which

Reginald de Lucy had in his charge; and having taken it, sacked it,

and then set it on fire, carrying away with him the burgesses

thereof.

At this period, Geoffrey, bishop elect of Lincoln, son of

king Henry, took the castle of Kinardeferie, and levelled it with the ground.

Also, Robert de Mowbray, the constable of the same castle, while

going towards Leicester to obtain assistance, was taken prisoner on

the road, by the people of Clay, and detained. Earl Hugh Bigot also

took the city of Norwich by storm, and burned it. In addition, to

this, the bishop elect of Lincoln, with Roger, the archbishop of

York, laid siege to Malasert, a castle belonging to Roger de Mowbray,

and took it, with many knights and men-at-arms therein, and gave it

into the charge of the archbishop of York. Before he departed, he

also fortified the castle of Topcliffe, which he delivered into the

charge of William de Stuteville.

* Called above, Roger: which is the name given by the other chroniclers

In the meantime, Richard, the archbishop elect of Canterbury,

and Reginald, the bishop elect of Bath, set out for Rome, for the purpose

of confirming their own elections and those of the other bishops

elect of England. To oppose them, king Henry, the son, sent to Rome

Master Berter, a native of Orleans. When the said parties had come

into the presence of pope Alexander, and the cardinals, and our lord

the pope had greatly censured the absence of the other bishops elect

of England, and the archbishop elect of Canterbury had done all in

his power to exculpate them, our lord the pope asked, with still

greater earnestness, why the bishop elect of Ely had not come; on

which Berter of Orleans made answer: “My lord, he has a

Scriptural excuse;"* to whom the pope made answer: “Brother,

what is the excuse?” on which the other replied: “He has

married a wife, and therefore cannot come.”

* Alluding to St. Luke xiv. 20.

In the end, however, although there was a great altercation

and considerable bandying of hard language on both sides before our lord

the pope and the cardinals, our lord the pope confirmed the election

of the archbishop of Canterbury: on which, Reginald, the bishop elect

of Bath, wrote to his master the king of England to the following

effect:

“To Henry, the illustrious king of England, duke of

Normandy and Aquitaine, and earl of Anjou, his most dearly beloved lord, Reginald,

by the grace of God, bishop elect of Bath, health in Him who gives

health to kings. Be it known to the prudence of your majesty, that,

at the court of our lord the pope, we found determined opponents from

the kingdom of France, and others still more determined from your own

territories. In consequence of this, we were obliged to submit to

many hardships there, and to make a tedious stay, till at last, at

our repeated entreaties, by the co-operation of the Divine grace, the

obduracy of our lord the pope was so far softened, that, in the

presence of all, he solemnly confirmed the election of the lord

archbishop elect of Canterbury; and after having so confirmed his

election, consecrated him on the Lord’s day following. On the

third day after his consecration, he gave him the pall, and a short

period of time having intervened, conferred on him the dignity of the

primacy. In addition to this, it being our desire that he should have

full power of inflicting ecclesiastical vengeance upon those men of

your realms who have iniquitously and in the treachery of their

wickedness, raised their heel against your innocence, we did, after

much solicitation, obtain the favour of the bestowal by our lord the

pope of the legateship on the same province. As for my own election,

and those of the others, they are matters still in suspense ; and our

lord the pope has determined to settle and determine nothing with

regard to us, until such time as your son shall have been brought to

a reconciliation. However, we put our trust in the Lord that the

interests of myself, and of all the other bishops elect, may be

safely entrusted to the prudent care of my lord the archbishop of

Canterbury."

In the same year, at the feast of the Nativity of Saint

John the Baptist, Richard de Lucy laid siege to the castle of Huntingdon, on

which the knights of that castle burned the town to the ground.

Richard de Lucy then erected a new castle before the gates of the

said castle of Huntingdon, and gave it in charge to earl Simon.

In the meanwhile, William, king of the Scots, laid siege to

Carlisle, of which Robert de Vals had the safe keeping; and, leaving a portion of

his army to continue the siege, with the remainder of it he passed

through Northumberland, ravaging the lands of the king and his

barons. He took the castle of Liddel, the castle of Burgh, the castle

of Appleby, the castle of Mercwrede, and the castle of Irebothe,

which was held by Odonel de Umfraville, after which he returned to

the siege of Carlisle. Here he continued the siege, until Robert de

Vals, in consequence of provisions failing him and the other persons

there, made a treaty with him on the following terms, namely, that,

at the feast of Saint Michael next ensuing, he would surrender to him

the castle and town of Carlisle, unless, in the meantime, he should

obtain succour from his master the king of England.

On this, the king of the Scots, departing thence, laid siege

to the castle of Prudhoe, which belonged to Odonel de Umfraville, but was

unable to take it. For Robert de Stuteville, sheriff of York, William

de Vesci, Ranulph de Glanville, Ralph de Tilly, constable of the

household of the archbishop of York, Bernard de Baliol, and Odonel de

Umfraville, having assembled a large force, hastened to its succour.

On learning their approach, the king of Scotland retreated

thence, and laid siege to the castle of Alnwick, which belonged to William de

Vesci, and then, dividing his army into three divisions, kept one

with himself, and gave the command of the other two to earl Dunecan

and the earl of Angus, and Richard de Morville, giving them orders to

lay waste the neighbouring provinces in all directions, slaughter the

people, and carry off the spoil. Oh, shocking times! then might you

have heard the shrieks of women, the cries of the aged, the groans of

the dying, and the exclamations of despair of the youthful!

In the meantime, the king of England, the son, and

Philip, earl of Flanders, came with a large army to Gravelines, for the

purpose of crossing over to England. On hearing of this, the king of England,

the father, who had marched with his army into Poitou, and had taken

many fortified places and castles, together with the city of Saintes,

and two fortresses there, one of which was called Fort Maror, as also

the cathedral church of Saintes, which the knights and men-at-arms

had strengthened against him with arms and a supply of provisions,

returned into Anjou, and took the town of Ancenis, which belonged to

Guion de Ancenis, near Saint Florence. On taking it, he strengthened

it with very strong fortifications, and retained it in his own hands,

and then laid waste the adjoining parts of the province with fire and

sword; he also rooted up the vines and fruit-bearing trees, after

which he returned into Normandy, while the king, his son, and Philip,

earl of Flanders, were still detained at Gravelines, as the wind was

contrary, and they were unable to cross over. On this, the king of

England, the father, came to Barbeflet,* where a considerable number

of ships had been assembled against his arrival, and, praised be the

name of the Lord! as it pleased the Lord, so did it come to pass;

who, by His powerful might, changed the wind to a favourable quarter,

and thus suddenly granted him a passage over to England. Immediately

on this, he embarked, and, on the following day, landed at

Southampton, in England, on the eight day before the ides of July,

being the second day of the week, bringing with him his wife, queen

Eleanor, and queen Margaret, daughter of Louis, king of the Franks,

and wife of his son Henry, with Robert, earl of Leicester, and Hugh,

earl of Chester, whom he immediately placed in confinement.

* Harfleur.

On the day after this, he set out on a pilgrimage to the

tomb of Saint Thomas the Martyr, archbishop of Canterbury. On his approach, as soon

as he was in sight of the church, in which the body of the blessed

martyr lay buried, he dismounted from the horse on which he rode,

took off his shoes, and, barefoot, and clad in woollen garments,

walked three miles to the tomb of the martyr, with such humility and

compunction of heart, that it may be believed beyond a doubt to have

been the work of Him who looketh down on the earth, and maketh it to

tremble. To those who beheld them, his footsteps, along the road on

which he walked, seemed to be covered with blood, and really were so;

for his tender feet being cut by the hard stones, a great quantity of

blood flowed from them on to the ground. When he had arrived at the

tomb, it was a holy thing to see the affliction which he suffered,

with sobs and tears, and the discipline to which he submitted from

the hands of the bishops and a great number of priests and monks.

Here, also, aided by the prayers of many holy men, he passed the

night, before the sepulchre of the blessed Martyr, in prayer,

fasting, and lamentations. As for the gifts and revenues which, for

the remission of his sins, he bestowed on this church, they can never

under any circumstance be obliterated from the remembrance thereof.

In the morning of the following day, after hearing mass, he departed

thence, on the third day before the ides of July, being Saturday,

with the intention of proceeding to London. And, inasmuch as he was

mindful of the Lord in his entire heart, the Lord granted unto him

the victory over his enemies, and delivered them captive into his

hands.

For, on the very same Saturday on which the king left Canterbury,

William, king of the Scots, was taken prisoner at Alnwick by the above-named

knights of Yorkshire, who had pursued him after his retreat from

Prudhoe. Thus, even thus; "How rarely is it that vengeance with

halting step forsakes the pursuit of the wicked!" Together with

him, there were taken prisoners Richard Cumin, William de Mortimer,

William de l’lsle, Henry Revel, Ralph de Ver, Jordan le

Fleming, Waltheof Fitz-Baldwin de Bicre, Richard Maluvel, and many

others, who voluntarily allowed themselves to be made prisoners, lest

they might appear to have sanctioned the capture of their lord.

On the same day, Hugh, count de Bar sur Seine, nephew of Hugh,

bishop of Durham, effected a landing at Herterpol* with forty knights and five

hundred Flemings, for whom the beforenamed bishop had sent; but in

consequence of the capture of the king of Scotland, the bishop

immediately allowed the said Flemings to return home, having first

given them allowance and pay for forty days. Count Hugh, however,

together with the knights who had come with him, he made to stay, and

gave the castle of Alverton** into their safe keeping.

*

Hartlepool. ** North Allerton.

These

things having taken place, Uctred, the son of Fergus, and Gilbert his

brother, the leaders of the men of Galloway, immediately upon the

capture of their lord the king of the Scots, returned to their

country, expelled the king’s thanes from their territories, and

slew without mercy those of English or French origin whom they found

therein. The fortresses and castles which the king of the Scots had

fortified in their territories they laid siege to, and, capturing

them, levelled them with the ground. They also earnestly entreated

the king of England, the father, at the same time presenting him many

gifts, to rescue them from the rule of the king of Scotland, and

render them subject to his own sway.

In the meantime, Louis, king of the Franks, hearing that the king of

England, the father, had crossed over, and that the king of Scots was

taken prisoner, with whose misfortunes he greatly condoled, recalled

the king of England the son, and Philip, earl of Flanders, who were

still staying at Gravelines; and after they had returned to him, laid

siege to Rouen on all sides, except that on which the river Seine

flows.

The king, the father, on hearing of the capture of the king of the Scots,

rejoiced with exceeding great joy, and after a thanksgiving to

Almighty God and the blessed martyr Thomas, set out for Huntingdon,

and laid siege to the castle, which was surrendered to him on the

Lord’s day following, being the twelfth day before the calends

of August. The knights and men-at-arms who were in the castle threw

themselves on the king’s mercy, safety being granted to life

and limb. Immediately upon this, the king departed thence with his

army towards Fremingham, the castle of earl Hugh Bigot; where the

earl himself was, with a large body of Flemings. The king, on drawing

nigh to Fremingham, encamped at a place which is called Seleham, and

remained there that night. On the following day, earl Hugh Bigot came

to him, and, making a treaty of peace with him, surrendered to him

the castle of Fremingham, and the castle of Bungay, and with

considerable difficulty obtained the king’s permission that the

Flemings who were with him. might without molestation return home. At

this place, the horse of Tostes de Saint Omer, a knight of the

Temple, struck the king on the leg, and injured him considerably. On

the following day, namely, on the seventh day before the calends of

August, the king departed from Seleham, and proceeded to Northampton;

on his arrival at which place William, king of the Scots, was brought

to him, with his feet fastened beneath a horse’s belly. There

also came to him Hugh, bishop of Durham, who delivered to him

possession of the castle of Durham, the castle of Norham, and the new

castle of Alverton, which he had fortified, and, after considerable

difficulty, obtained permission that his nephew, the count de Bar,

and the knights who had come with him, might return to their own

country. Roger de Mowbray also came thither to him, and surrendered

to him the castle of Tresk,* and the earl of Ferrers delivered up to

him the castles of Tutesbury,** and of Duffield; Anketill Mallory

also and William de Dive, constables of the earl of Leicester,

surrendered to him the castles of Leicester, of Mountsorrel, and of

Groby.

*

Thirsk ** Tutbury

Thus

then, within the space of three weeks, was the whole of England

restored to tranquillity, and all its fortified places delivered into

the king’s hands. These matters being arranged to his

satisfaction, he speedily crossed over from England to Normandy, and

landed at Barbeflet on the sixth day before the ides of August, being

the fifth day of the week, taking with him his Brabanters and a

thousand Welshmen, together with William, king of the Scots, Robert,

earl of Leicester, and Hugh, earl of Chester, whom he placed in

confinement, first at Caen, and afterwards at Falaise.

On the same day on which the king landed at Barbeflet, he met on the

sea-shore Richard, archbishop of Canterbury, on his return from

Alexander, the Supreme Pontiff, with the pall and legateship and

primacy of the whole of England, together with Reginald, bishop of

Bath, whom the said archbishop had consecrated at Saint John de

Maurienne, on their return from Rome. The king, however, did not wish

to detain them with him, but sent them on to England. After this, on

the Lord’s day next ensuing, the king, the father, arrived with

his Brabanters and Welchmen at Rouen, which the king of France and

the king of England, the son, were besieging on one side, while on

the other there was free egress and ingress. On the following

morning, the king sent his Welchmen beyond the river Seine; who,

making way by main force, broke through the midst of the camp of the

king of France, and arrived unhurt at the great forest, and on the

same day slew more than a hundred of the men of the king of France.

Now,

the king of France had been staying there hardly a month, when, lo!

the king of England, the father, coming from England, opened the

gates of the city, which the burgesses had blocked up, and sallying

forth with his knights and men-at-arms, caused the fosses which had

been made between the army of the king of France and the city, to be

filled up with logs of timber, stones, and earth, and to be thus made

level. As for the king of France, he and his men remained in their

tents, and were not inclined to come forth. The rest of the people of

the king of England took up their positions for the defence of the

walls, but no one attacked them; however, a part of the army of the

king of France made an attempt to destroy their own engines of war.

On

the following day, early in the morning, the king of France sent the

weaker portion of his army into his own territories; and, with the

permission of the king of England, followed them on the same day to a

place which is called Malaunay, and lies between Rouen and the town

called Tostes; having first given security by the hand of ‘William,

archbishop of Sens, and of earl Theobald, that on the following day

he would return to confer with the king of England on making peace

between him and his sons. The king of France, however, did not keep

his engagement and his oath, and did not come on the following day to

the conference, but departed into his own territories.

However,

after the expiration of a few days, he again sent the above-named

archbishop of Sens and earl Theobald to the king of England,

appointing a day for the conference, to be held at Gisors, on the

Nativity of Saint Mary. When they met there they could not come to an

agreement, on account of Richard, earl of Poitou, who was at this

time in Poitou, besieging the castles and subjects of his father. In

consequence of this, they again held another conference between them,

upon the festival of Saint Michael, between. Tours and Amboise, on

which occasion they agreed to a truce on these terms: that the said

Richard, earl of Poitou, should be excluded from all benefit of the

truce, and that the king of France and the king of England, the son,

should give him no succour whatever. Upon these arrangements being

made on either side, the king of England, the father, moved on his

army into Poitou; on which, Richard, earl of Poitou, his son, not

daring to await his approach, fled from place to place. When he

afterwards came to understand that the king of France, and the king,

his brother, had excluded him from the benefit of the truce, he was

greatly indignant thereat; and, coming with tears, he fell on his

face upon the ground at the feet of his father, and imploring pardon,

was received into his father’s bosom. These events took place

at Poitou, on the eleventh day before the calends of October, being

the second day of the week; and thus, the king and his son Richard

becoming reconciled, they entered the city of Poitou.

After

this, they both set out together for a conference held between Tours

and Amboise, on the day before the calends of October, being the

second day of the week and the day after the feast of Saint Michael.

Here the king, the son, and Richard and Geoffrey, his brothers, by

the advice and consent of the king and barons of France, made the

treaty of peace underwritten with the king their father:

“Be

it known unto all present as well as to come, that, by the will of

God, peace has been made between our lord the king and his sons,

Henry, Richard, and Geoffrey, on the following terms:—Henry,

the king, the son of the king, and his brothers aforesaid, have

returned unto their father and to his service us their liege lord,

free and absolved from all oaths whatsoever which they have made

between themselves, or with any other persons, against him, or

against his subjects. All liegemen and barons who, for their sake,

have abandoned their fealty to their father, they have released from

all oaths whatsoever which they have made to themselves; and, freely

acquitted from all oaths and absolved from all covenants which they

had made to them, the same have returned to their homage and

allegiance to our lord the king. Also, our lord the king, and all his

liegemen and barons, are to receive possession of all their lands and

castles which they held fifteen days before his sons withdrew from

him. So, in like manner, his liegemen and barons who withdrew from

him and followed his sons, are to receive possession of their lands

which they had fifteen days before they withdrew from him. Also, our

lord the king has laid aside all displeasure against his barons and

liegemen who withdrew from him, so that by reason thereof he will do

no evil to them, so long as they shall faithfully serve him as their

liege lord. And, in like manner, the king, his son, has pardoned all,

both clerks as well as laymen, who took part with his father, and has

remitted all displeasure against them, and has given security into

the hand of our lord the king, his father, that he will not do, or

seek to do, in all his life any evil or harm to those who obeyed him,

by reason of their so doing.

“Also,

upon these conditions, the king gives to the king, his son, two

suitable castles in Normandy, at the option of his father, and

fifteen thousand pounds, Anjouin, yearly revenue. Also, to his son

Richard he gives two suitable mansions in Poitou, whence evil cannot

ensue to the king, and a moiety of the revenues of Poitou in ready

money. To his son Geoffrey he gives, in ready money, the moiety of

what he would receive in Brittany on his marriage with the daughter

of earl Conan, whom he is to take to wife; and after, by the license

of the Roman Church, he shall have taken her to wife, then he shall

have the whole of the revenues accruing by that marriage, in such

manner as is set forth in the deed executed by earl Conan. But, as to

the prisoners who have made a composition with our lord the king

before this treaty was made with our lord the king, namely, the king

of Scotland, the earl of Leicester, the earl of Chester, and Ralph de

Fourgeres, and their pledges, and the pledges of the other prisoners

whom he had before that time, they are to be excepted out of this

treaty. The other prisoners are, however, to be set at liberty on

both sides; but upon the understanding that our lord the king shall

take hostages as pledges from such of his prisoners as he shall think

fit, and shall be able to give the same; and from the rest he shall

take security by the assurance and oaths of themselves and of their

friends. As for the castles which have been built or fortified in the

territories of our lord the king since the war began, they are,

subject to the king’s wishes thereon, to be reduced to the same

state in which they were fifteen days before the war began. Further,

be it known, that king Henry, the son, has covenanted with our lord

the king, his father, that he will strictly observe all gifts in

almoign which he has given, or shall give, to his liegemen for their

services. He has also covenanted that he will strictly and inviolably

confirm the gifts which the king, his father, has made to his brother

John; namely, a thousand pounds of yearly revenues out of his demesne

lands and echeats in England at his own option, together with their

appurtenences; also a castle of Nottingham with the county thereof,

and the castle of Marlborough with its appurtenences; also in

Normandy, one thousand pounds, Anjouin, of yearly revenue and two

castles in Normandy at the option of his father; and in Anjou and the

lands which belonged to the earl of Anjou, one thousand pounds,

Anjouin, of revenue, as also one castle in Anjou, one castle in

Touraine, and one castle in Maine. It has also been covenanted by our

lord the king, in the love which he bears to his son, that all those

who withdrew from him after his son, and offended him by such

withdrawal, may return into the territories of our lord the king

under his protection. Also, for the chattels which on such withdrawal

they carried away, they shall not be answerable: as to murder, or

treason, or the maiming or any limb, they are to be answerable

according to the laws and customs of the land. Also, as to those who

before the war took to flight for any cause, and then entered the

service of his son, the same may, from the love he bears to his son,

return in peace, if they give pledge and surety that they will abide

their trial for those offences of which, before the war, they have

been guilty. Those, also, who were awaiting trial at the time when

they withdrew to his son, are to return in peace, upon condition that

their trials are to be in the same state as when they withdrew.

Henry, the king, the son of our lord the king, has given security

into the hands of his father that this agreement shall on his part be

strictly observed. And, further, Henry, the king’s son, and his

brothers, have given security that they will never demand of our lord

the king, contrary to the will and good pleasure of our lord the

king, their father, anything whatever beyond the gifts above-written

and agreed upon, and that they will withdraw neither themselves nor

their services from their father. Also, Richard, and Geoffrey, his

brother, have done homage to their father for those things which he

has given and granted unto them : and, whereas his son, Henry, was

ready and willing to do homage to him, our lord the king was

unwilling to receive the same of him, because he was a king; but he

has received security from him for the same.”

In

the same year, a dissension arose between Uctred and Gilbert, the

sons of Fergus, and chieftains of the men of Galloway, on which

Malcolm, the son of Gilbert, took Uctred by treachery, and, after

depriving him of his virility and putting out his eyes, caused him to

be put to death.

In this year, [1174] also, Richard, archbishop of Canterbury,

consecrated, in England, at Canterbury, Richard, bishop of

Winchester, Robert Folliot, bishop of Hereford, Geoffrey Riddel,

bishop of Ely, and John, bishop of Chichester. In the same year,

nearly the whole of the city of Canterbury was burned to the ground,

together with the metropolitan church of the Holy Trinity. In this

year, also, died William Turbe, bishop of Norwich.

In

the same year, peace and final reconciliation were established

between Roger, archbishop of York, and Hugh, bishop of Durham, upon

the following terms: “The chapel and burial ground of Alverton

shall remain in the hands of the prior of Hexham, on condition that

the archbishop shall not insist on any person being buried there, nor

shall the bishop hinder it. The church of Hexham shall receive the

chrism and oil from the bishop of Durham, according to its present

usage : the prior of Hexham shall also attend the synod of Durham..

The

clerks and canons of Hexham shall receive ordination from the bishop

of Durham. The parishioners of Hexham, at the time of Pentecost, if

they shall think fit, shall visit the church of Durham without any

compulsion on the part of the bishop or of his people, and without

any prohibition on the part of the archbishop or of his people. Also,

if their people shall presume to act contrary to this, their masters

themselves shall correct them. The prior of Hexham shall try all

ecclesiastical causes of that parish, without power to inflict fines,

though with liberty to impose penance. On the decease of the present

prior, Richard, the bishop of Durham, shall have the same authority

in the appointing of another prior, which the said prior, Richard,

and the prior of Gisburne, and Peter, brother of the prior of

Bridlington, have sworn that the church of Durham had in the

appointing of the said prior, Richard, if indeed they shall have

sworn that it had any. The archbishop shall not demand synodal fees

of the churches of Saint Cuthbert, the names of which, in the

archdeaconry of Cleveland, are as follow: the church of Hemmingburgh,

the church of Schepwick, the church of Alverton, the church of

Bretteby, the church of Osmunderley, the church of Seigestun, the

church of Lee, the church of Oterington, the church of Crake, and the

church of Holteby; in the archdeaconry of York; the church of All

Saints in Ousegate, the church of Saint Peter the Little, and half of

the church of the Holy Trinity, in Sudersgate; and, in the

archdeaconry of the treasurer; the church of Hoveden, *

the church of Welleton, the church of Brentington, and the church of

Walkinton. But if the clergy of the said churches, or the laity of

the demesne manors of Saint Cuthbert, situate in Yorkshire, shall be

guilty of anything that deserves ecclesiastical correction, the same

shall be amended by the archbishop, such a summons being first

issued, that the bishop or his officer shall he able to be present

thereat.” The above articles were confirmed by the archbishop

and the bishop, who mutually gave their word that they would, without

fraud or deceit, observe the same so long as they two should live,

and without prejudice to the church of either after the decease of

the other. In addition to which, the archbishop similarly gave his

word to the bishop that he would in no matter

annoy him or his church, or any one in his bishopric, until the cause

should have been first taken open cognizance of in due course of

judgment.

* Howden, in Yorkshire, the native place of our author.

1175 A.D.

In the year of grace 1175, being the twenty-first year of the

reign of king Henry the Second, son of the empress Matilda, the said king was

at Argenton, in Normandy, during the festival of the Nativity of our

Lord. At the Purification of Saint Mary, he and the king, his son,

were at Le Mans, whence they returned into Normandy, and held a

conference with Louis, king of the Franks, at Gisors. Having come

thence to Bure in Normandy, the king, the son, in order that he might

remove all mistrust from his father’s mind, did homage to him

as his liegeman, and swore fealty to him against all men, in the

presence of Rotrod, archbishop of Rouen, Henry, bishop of Bayeux,

William, earl of Mandeville, and Richard de Humez, his constable, and

many other persons of the household of both kings.

At

the festival of Easter, the two kings were at Caesar’s Burgh,*

and, after Easter, they proceeded to Caen to meet Philip, earl of

Flanders, who shortly before had assumed the cross of the pilgrimage

to Jerusalem. The king, the father, prevailed upon him to release the

king, the son, from all covenants which he had made with him during

the period of the hostilities ; and the earl of Flanders delivered

into the king’s hands the documents of the king, the son, which

he had relative to the above-named covenants. On this, they confirmed

to the earl the yearly revenues which he had been in the habit of

receiving in England before the war.

*

Cherbourg.

The king, the father, also sent his son Richard into Poitou, and his son

Geoffrey into Brittany, with orders that the castles which had been

built or fortified during the time of the war, should be reduced to

the same state in which they were fifteen days before the war began.

After this, the king, the father, and the king, the son, crossed

over, and landed in England, at Portsmouth, on the seventh day before

the ides of May, being the sixth day of the week. On coming to

London, they found Richard, archbishop of Canterbury, about to hold a

synod at Westminster on the Lord’s day before the Ascension of

our Lord ; to which synod came nearly all the bishops and abbats of

the province of Canterbury. Before the kings above-named, and the

bishops and abbots, Richard, the archbishop of Canterbury, standing

on an elevated place, published the decrees underwritten:

“Synods are called together in the Church of God, in conformity with the

ancient usage of the fathers, in order that those who are appointed

to the higher office of the pastoral charge, may, by institutions

based upon rules subjected to their common consideration, reform the

lives of those submitted to their care, and, with a judgment better

informed, be able to check those enormities which are incessantly

springing up. We therefore, rather adhering to the rules of our

forefathers who adhered to the true faith, than devising anything

new, have thought it advisable that certain definite heads should be

published by us; which by all of our province we do enjoin to be

strictly and inviolably observed. For all those who shall presume to

contravene the enactments of this holy synod, we deem to be

transgressors of the sacred canons.

“If any priest or clerk in holy orders, having a church or ecclesiastical

benefice, shall publicly keep a harlot, and after being warned

thereon a first, second, and third time, shall not put away his

harlot, and entirely separate himself from her, but shall rather

think fit to persist in his uncleanness, he shall be deprived of all

ecclesiastical offices and benefices. But if any persons below the

rank of sub-deacons shall have contracted marriage, let them not by

any means be separated from their wives, except with their common

consent that they shall do so and enter a religious order, and there

let them with constancy remain in the service of God. But if any

persons of the rank of sub-deacon or above the same, shall have

contracted marriage, let them leave their wives, even though they

should be unwilling and reluctant. Also, on the authority of the same

epistle we have decreed, that the sons of priests are not,

henceforth, to be instituted as clergymen in the churches of their

fathers; nor are they, under any circumstances whatsoever, to hold

the same without the intervention of some third person.*

* Taken from the decretal epistle of pope Alexander III to Roger,

bishop of Worcester.

“Clerks in holy orders are not to enter taverns for the purpose of eating and

drinking, nor to be present at public drinkings, unless when

travelling, and compelled by necessity. And if any one shall be

guilty of so doing, either let him put an end to the practice, or

suffer deprivation.*

* From the decrees of the council of Carthage.

“Those who are in holy orders are not allowed to give judgment on matters of

life and death. Wherefore, we do forbid them either themselves to

take part in dismemberment, or to order it to be done by others. And

if any one shall be guilty of doing such a thing, let him be deprived

of the office and position of the orders that have been granted to

him. We do also forbid, under penalty of excommunication, any priest

to hold the office of sheriff, or that of any secular public officer.*

* From the decrees of the council of Toledo.

“Clerks who allow their hair to grow, are, though against their will, to be

shorn by the archdeacon. They are also not to be allowed to wear any

garments or shoes, but such as are consistent with propriety and

religion. And if any one shall presume to act contrary hereto, and on

being warned shall not be willing to reform, let him be subject to

excommunication.*

* From the decrees of the council of Agatha

“Inasmuch as certain clerks, despairing of obtaining ordination from their own

bishops, either on account of ignorance, or irregularity of life, or

the circumstances of their birth, or a defect in their title, or

youthful age, are ordained out of their own province, and sometimes

even by bishops beyond sea, or else falsely assert that they have

been so ordained, producing unknown seals to their own bishops; we do

enact that the ordination of such shall be deemed null and void, and,

under pain of excommunication, we do forbid that they shall be

employed by any one in the performance of his duties. The bishop

also, within our jurisdiction, who knowingly and wilfully shall

ordain any such person or employ him after the conferring of such

orders, for so ordaining or employing him, let him know that he is suspended

from his office until he shall have made due satisfaction. Likewise,

inasmuch as the Church of God, according to the verity of the Gospel,

ought to be the house of prayer, and not a den of thieves, and market

for blood; under pain of excommunication we do forbid secular causes,

in which the shedding of blood or bodily punishment is likely to be

the result, to be tried in churches or in churchyards. For it is

absurd and cruel for judgment of bloodshed to be discussed in the

place which has also been appointed a place of refuge for the

guilty.*

* From various decrees of popes Urban and Innocent, and of

the councils of Chalcedon and Carthage.

“It has been told us, that it is the custom in some places for money to

be given for receiving the chrism, as also for baptism and the

communion. This as a simoniacal heresy a holy council held in

detestation, and visited with excommunication. We do therefore enact,

that in future nothing shall be demanded either for ordination, or

for the chrism, or for baptism, or for extreme unction, or for